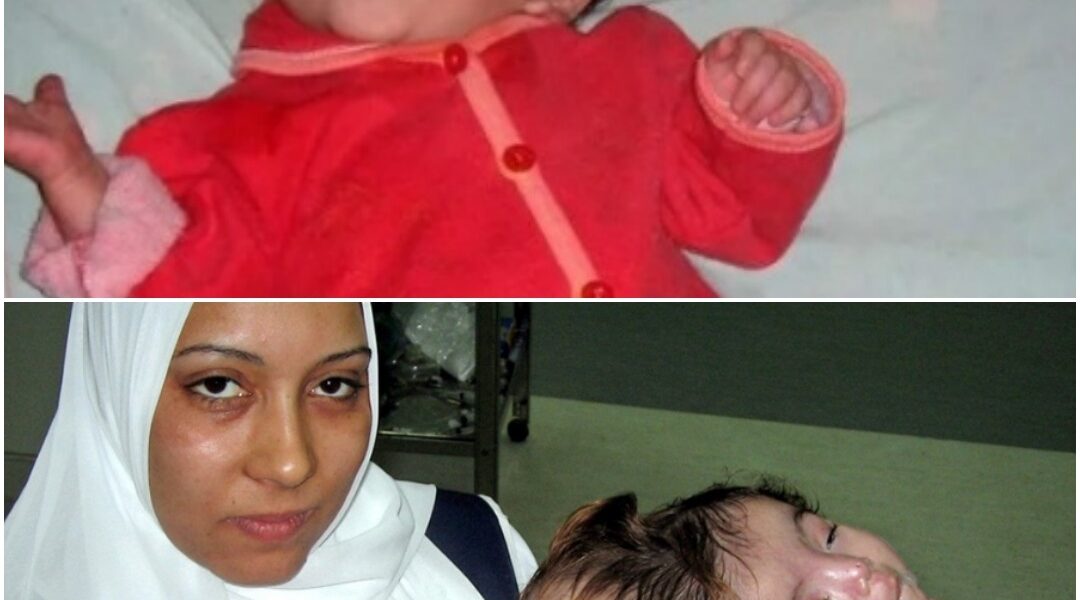

Born With Two Heads And One Fragile Body An Egyptian Infant Changed Modern Medicine Forever . Hyn

The Boy Whose Skull Was Split in Two and the Miracle That Let Him Play Again

One day after his first birthday, Archie Dodd was supposed to be doing what toddlers do best. He should have been wobbling across the floor, laughing at his older brothers, discovering the world with the fearless curiosity of a child who has no idea how fragile life can be.

Instead, his parents were being told that something was terribly wrong with his head.

Not a bump. Not a bruise. Not something that would heal on its own.

Something rare. Something dangerous. Something that could change the course of his life forever.

Archie was just three years old when doctors in Chesterfield, England, diagnosed him with craniosynostosis, a rare condition in which the bones of the skull fuse together too early. In a healthy child, those bones remain flexible, allowing the brain to grow and expand. In Archie’s case, his skull had begun to close in on itself.

His head was, in effect, becoming a cage.

As his brain continued to grow, there would be nowhere for it to go. Pressure would build. Development could be compromised. In the worst-case scenario, the damage could be permanent.

For his parents, the diagnosis felt unreal. Archie had been their bright, energetic little boy. He laughed easily. He chased his brothers. He showed no sign that his own skull was quietly working against him.

But scans do not lie.

The family was referred immediately to Sheffield Children’s Hospital, where specialists confirmed the severity of the condition. The solution, they explained, was as terrifying as it was necessary.

Archie’s skull would need to be opened.

Not partially. Not delicately.

It would need to be cut from ear to ear in a zigzag pattern, the bone separated into pieces, reshaped, and then reassembled like a three-dimensional puzzle. Only then could his brain have the space it needed to grow safely.

It was not cosmetic surgery. It was not optional.

It was the only way to save his future.

For most parents, the idea of brain surgery on a toddler is almost impossible to process. The thought of saws and scalpels near something so small, so precious, feels unbearable.

Archie’s parents were told the risks honestly. Blood loss. Infection. Swelling. Neurological damage. Even death.

But they were also told what would happen if they did nothing.

And so they agreed.

The operation was long and complex. Surgeons carefully opened Archie’s skull, working with precision that left no room for error. Each cut was deliberate. Each movement calculated.

When the surgery was finally complete, Archie’s skull had been reshaped to allow his brain to develop normally. The immediate danger had passed.

But the recovery was only beginning.

Because the bones of his skull were still fragile, Archie could not simply return to normal life. His head needed protection every moment of the day.

For six months, he wore a helmet.

Not for sports. Not for play.

For survival.

The helmet became part of Archie’s identity. It followed him everywhere — around the house, outside, into daily life. It protected the healing bones beneath, shielding the most vulnerable part of him while his skull slowly regained strength.

To strangers, it may have looked unusual. To his parents, it was reassurance.

Every time they fastened it into place, they were reminded of how close they had come to losing everything.

Recovery was not instant. There were follow-up scans. Checkups. Long waits filled with quiet anxiety.

But slowly, steadily, Archie healed.

His skull strengthened. His development continued. His laughter returned without fear.

And one day, something remarkable happened.

Archie ran.

He kicked a football.

He played with his brothers like any other child.

The helmet came off.

The image of Archie playing football after months of protection is more than a feel-good ending. It is proof of what modern medicine, courage, and early intervention can do when everything goes right.

Craniosynostosis is rare, and many families never recognize the signs until it is too late. Archie’s story is a reminder of how fragile childhood can be — and how resilient it can also be.

Today, Archie is doing well. His recovery has been described as strong and steady. His life, once threatened by a skull that would not grow with him, now moves forward with possibility.

The scars remain, faint reminders of a battle he was too young to remember but will forever carry in his story.

For his parents, there is no forgetting the fear. The waiting. The sound of hospital corridors. The moment they handed their child over to surgeons and trusted that skill and hope would be enough.

For Archie, there is only life.

Running. Playing. Laughing.

A little boy who once had his skull split in two — and who lived to chase a ball across the grass.