He Slipped Beneath the Water in Silence: The Tragedy That Revealed How Drowning Really Happens. Hyn

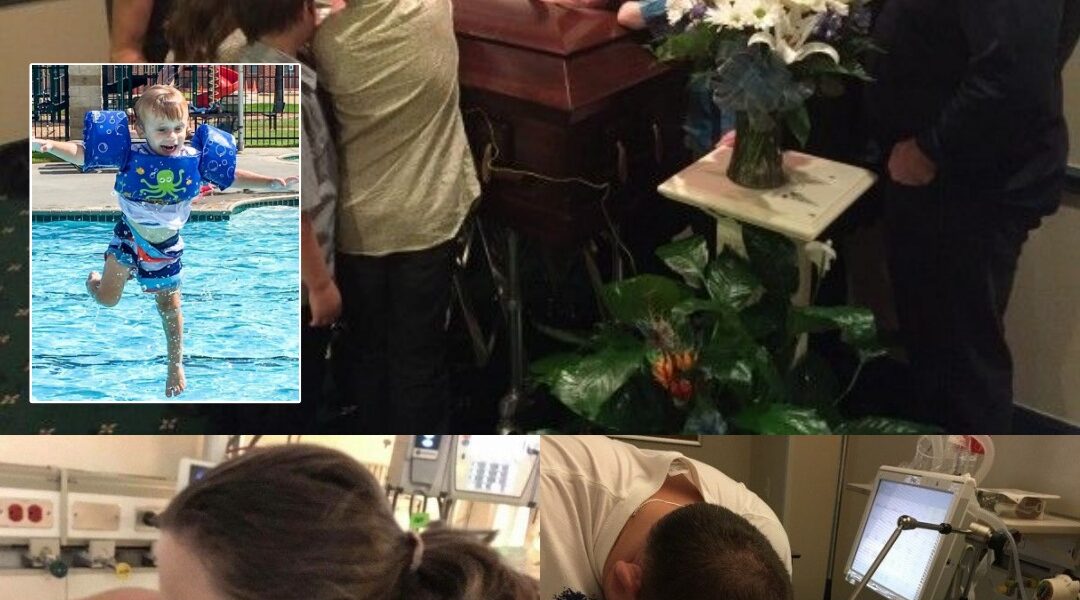

Judah Levi Brown was the kind of child who filled every room without trying, the kind whose laughter arrived before he did and lingered long after he left.

He was lively, happy, endlessly curious, and wildly adventurous, a blue-eyed, blonde-haired firecracker who was always into something — and most of the time, into everything. He loved life with his whole heart and soaked up every second of it as if he somehow knew that childhood was precious and fleeting.

Being around Judah made people smile without effort.

He was kind in the purest way, the kind of child who wanted to know everyone’s name, who greeted the world with openness instead of fear. He loved zebras and elephants, Paw Patrol, chocolate, and most of all, spending time with his momma, his daddy, and his six siblings who made up his entire universe.

And more than anything else…

Judah loved the water.

He was a true water baby, the kind of child who could spend all day splashing, floating, laughing, and playing if his momma would let him. Because his love for water was so obvious, his parents did what they believed responsible parents were supposed to do.

They got him swimming lessons early.

They were told he had been taught how to rescue himself if he ever needed to. They practiced those skills with him regularly. They paid attention. They tried to do everything right. They layered safety on top of safety, believing that preparation would protect their boy.

They never imagined that even with all of that… it still would not be enough.

The day Judah died is a day his family still struggles to comprehend.

It was supposed to be ordinary.

They were at a friend’s BBQ at an apartment complex, gathered around a familiar pool, surrounded by laughter, food, and the comfortable chaos of children playing together. All of their kids were swimming, including Judah, who was wearing a puddle jumper — something his mom believed would keep him safe.

For about twenty minutes, Judah laughed and played with his siblings and friends, kicking, splashing, and enjoying the water the way he always did. Eventually, he grew cold and climbed out of the pool, asking for a drink and his towel.

His mom tried to wrap him up, but Judah wiggled and resisted, as little boys do. To dry him properly, she made a decision that would haunt her forever.

She took off his puddle jumper.

It felt harmless. Logical. Temporary.

She wrapped him in a towel, warmed him up, and helped him find a chair to sit in right next to her. The adults were sitting close to the pool, watching the kids, periodically counting heads, doing what they believed was attentive supervision.

Judah wanted his mom’s chair.

He tried to push her out of it, and she laughed, teasing him, telling him he was being bossy.

She didn’t know those would be the last words her son would ever hear her say.

She sat him back down and turned her attention to the pool again, talking briefly with a friend. In that tiny window of time — a minute, maybe less — Judah slipped away from his chair without anyone noticing.

He went back into the pool.

Without his puddle jumper.

When they counted heads again, Judah was missing.

Panic arrived instantly.

They ran, calling his name, searching everywhere.

“Judah… baby boy… JuJu…”

Seconds stretched into something unbearable.

Then she saw him.

Judah was in the pool, just past the stairs, completely submerged, motionless, lifeless. He was already sinking toward the bottom, which she would later learn meant his lungs had almost completely filled with water.

Her body froze.

Her mind shattered.

She could not move, could not think, could not process what her eyes were seeing. She stood there shaking uncontrollably, screaming his name, begging God aloud not to take her baby.

“NOT MY BABY… PLEASE… NOT MY BABY…”

A friend rushed past her and pulled Judah from the water.

His small body was limp.

His skin was purple and blue.

He wasn’t breathing.

There was no heartbeat.

Someone called 911 as Judah’s father and the friend’s husband took turns performing CPR, desperately trying to bring life back into a body that felt impossibly still. The ambulance arrived nine minutes later — nine minutes that felt like an eternity.

Judah’s mother screamed for them to move faster, unable to understand why the world seemed to be moving in slow motion when her child was dying.

Someone later told her they were moving fast.

At some point, paramedics managed to restart Judah’s heart, and the family made the long, horrifying drive to the best pediatric trauma hospital in Houston. Judah would spend the next two and a half days in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, on life support, in critical condition.

Doctors estimated that Judah had been in cardiac arrest for about thirty-five minutes, most of that time spent trying to resuscitate him.

From the beginning, the prognosis was devastating.

They told his parents that Judah had been without oxygen to his brain for too long. He had less than a thirty percent chance of survival. And even if he did survive, he would likely suffer severe brain damage and be dependent on machines for nearly everything for the rest of his life.

The words were spoken.

But they did not register.

His mother could not understand how a vibrant little boy who had been splashing in the pool and trying to steal her chair less than an hour earlier was now lying in a coma, unable to regulate his own body temperature.

It felt impossible.

Unreal.

Wrong.

All they could do was wait.

So they waited.

They watched the machines.

They held each other.

They held Judah’s cold hand.

His mother begged him to move his fingers, even just a little, to give her a sign that he was still there, still fighting. She remembered the strength he had shown from the moment he was born, climbing up her chest in his first moments of life, and she begged God to let that same strength save him now.

For a day and a half, doctors noticed a slight reaction in Judah’s left pupil — a sign of minimal brain activity, a fragile thread of hope the family clung to desperately.

Then it disappeared.

The MRI results were undeniable.

Judah’s brain could not withstand the damage.

He was gone.

His siblings were brought in to see him one last time. Doctors completed the first official brain death assessment. Judah failed it. Twelve hours later, they performed another.

He failed that one too.

A nuclear scan showed no blood flowing to his brain.

Judah was declared brain dead.

His parents were taken into a quiet, cold office to begin discussing organ donation — the unimaginable decision to give their son’s brave heart and precious organs to save other children’s lives.

Then a doctor interrupted.

Judah had gone into cardiac arrest again.

They brought him back.

Minutes later, chaos erupted in his room.

“This is too much for his body,” a doctor said. “I’m calling it.”

Judah’s heart stopped for the third and final time.

It could not endure any more.

Judah Levi Brown died at 9:51 p.m. on September 26, 2016.

They buried him the following week.

He was the youngest of seven children.

The only child his parents had together.

Their last baby.

Their Judah-bug.

While sitting helplessly in the PICU, watching her son die, Judah’s mother learned something that filled her with rage on top of grief.

Drowning is the number one cause of accidental death for children ages one to four.

It is the number two cause for children ages four to fourteen.

Boys are seventy-seven percent more likely to drown than girls.

She had never been told this before.

Not by pediatricians.

Not by schools.

Not by parenting books.

Car seat safety is drilled into parents from pregnancy onward — yet drowning is fourteen times more likely to kill a child than a car accident.

Why wasn’t anyone talking about this?

Why did she only learn when her child was already dying?

Out of unimaginable loss, something unexpected began to grow.

Judah’s preschool teacher reached out, wanting to organize a fundraiser to help with the overwhelming medical bills. That small act grew into something much larger — The Judah Brown Project, a foundation built to ensure other parents would never have to learn these lessons the way Judah’s family did.

Today, Judah’s legacy lives on.

Through water safety education.

Through survival swim lessons for families who cannot afford them.

Through pamphlets in pediatric offices across the country.

Through training for parents, caregivers, teachers, and professionals.

Through a message that saves lives.

Because drowning is fast.

Because drowning is silent.

Because puddle jumpers create false confidence.

Because children cannot understand risk the way adults assume they can.

Because real water safety requires multiple layers of protection.

Judah’s story exists so that other children can live.

His life was short.

But his legacy is powerful.

And through every child saved, Judah Levi Brown is still here — still teaching, still protecting, still reminding the world that silence around water can be deadly, and that awareness can mean the difference between life and loss.

Page 2

Judah Levi Brown was the kind of child who filled every room without trying, the kind whose laughter arrived before he did and lingered long after he left.

He was lively, happy, endlessly curious, and wildly adventurous, a blue-eyed, blonde-haired firecracker who was always into something — and most of the time, into everything. He loved life with his whole heart and soaked up every second of it as if he somehow knew that childhood was precious and fleeting.

Being around Judah made people smile without effort.

He was kind in the purest way, the kind of child who wanted to know everyone’s name, who greeted the world with openness instead of fear. He loved zebras and elephants, Paw Patrol, chocolate, and most of all, spending time with his momma, his daddy, and his six siblings who made up his entire universe.

And more than anything else…

Judah loved the water.

He was a true water baby, the kind of child who could spend all day splashing, floating, laughing, and playing if his momma would let him. Because his love for water was so obvious, his parents did what they believed responsible parents were supposed to do.

They got him swimming lessons early.

They were told he had been taught how to rescue himself if he ever needed to. They practiced those skills with him regularly. They paid attention. They tried to do everything right. They layered safety on top of safety, believing that preparation would protect their boy.

They never imagined that even with all of that… it still would not be enough.

The day Judah died is a day his family still struggles to comprehend.

It was supposed to be ordinary.

They were at a friend’s BBQ at an apartment complex, gathered around a familiar pool, surrounded by laughter, food, and the comfortable chaos of children playing together. All of their kids were swimming, including Judah, who was wearing a puddle jumper — something his mom believed would keep him safe.

For about twenty minutes, Judah laughed and played with his siblings and friends, kicking, splashing, and enjoying the water the way he always did. Eventually, he grew cold and climbed out of the pool, asking for a drink and his towel.

His mom tried to wrap him up, but Judah wiggled and resisted, as little boys do. To dry him properly, she made a decision that would haunt her forever.

She took off his puddle jumper.

It felt harmless. Logical. Temporary.

She wrapped him in a towel, warmed him up, and helped him find a chair to sit in right next to her. The adults were sitting close to the pool, watching the kids, periodically counting heads, doing what they believed was attentive supervision.

Judah wanted his mom’s chair.

He tried to push her out of it, and she laughed, teasing him, telling him he was being bossy.

She didn’t know those would be the last words her son would ever hear her say.

She sat him back down and turned her attention to the pool again, talking briefly with a friend. In that tiny window of time — a minute, maybe less — Judah slipped away from his chair without anyone noticing.

He went back into the pool.

Without his puddle jumper.

When they counted heads again, Judah was missing.

Panic arrived instantly.

They ran, calling his name, searching everywhere.

“Judah… baby boy… JuJu…”

Seconds stretched into something unbearable.

Then she saw him.

Judah was in the pool, just past the stairs, completely submerged, motionless, lifeless. He was already sinking toward the bottom, which she would later learn meant his lungs had almost completely filled with water.

Her body froze.

Her mind shattered.

She could not move, could not think, could not process what her eyes were seeing. She stood there shaking uncontrollably, screaming his name, begging God aloud not to take her baby.

“NOT MY BABY… PLEASE… NOT MY BABY…”

A friend rushed past her and pulled Judah from the water.

His small body was limp.

His skin was purple and blue.

He wasn’t breathing.

There was no heartbeat.

Someone called 911 as Judah’s father and the friend’s husband took turns performing CPR, desperately trying to bring life back into a body that felt impossibly still. The ambulance arrived nine minutes later — nine minutes that felt like an eternity.

Judah’s mother screamed for them to move faster, unable to understand why the world seemed to be moving in slow motion when her child was dying.

Someone later told her they were moving fast.

At some point, paramedics managed to restart Judah’s heart, and the family made the long, horrifying drive to the best pediatric trauma hospital in Houston. Judah would spend the next two and a half days in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, on life support, in critical condition.

Doctors estimated that Judah had been in cardiac arrest for about thirty-five minutes, most of that time spent trying to resuscitate him.

From the beginning, the prognosis was devastating.

They told his parents that Judah had been without oxygen to his brain for too long. He had less than a thirty percent chance of survival. And even if he did survive, he would likely suffer severe brain damage and be dependent on machines for nearly everything for the rest of his life.

The words were spoken.

But they did not register.

His mother could not understand how a vibrant little boy who had been splashing in the pool and trying to steal her chair less than an hour earlier was now lying in a coma, unable to regulate his own body temperature.

It felt impossible.

Unreal.

Wrong.

All they could do was wait.

So they waited.

They watched the machines.

They held each other.

They held Judah’s cold hand.

His mother begged him to move his fingers, even just a little, to give her a sign that he was still there, still fighting. She remembered the strength he had shown from the moment he was born, climbing up her chest in his first moments of life, and she begged God to let that same strength save him now.

For a day and a half, doctors noticed a slight reaction in Judah’s left pupil — a sign of minimal brain activity, a fragile thread of hope the family clung to desperately.

Then it disappeared.

The MRI results were undeniable.

Judah’s brain could not withstand the damage.

He was gone.

His siblings were brought in to see him one last time. Doctors completed the first official brain death assessment. Judah failed it. Twelve hours later, they performed another.

He failed that one too.

A nuclear scan showed no blood flowing to his brain.

Judah was declared brain dead.

His parents were taken into a quiet, cold office to begin discussing organ donation — the unimaginable decision to give their son’s brave heart and precious organs to save other children’s lives.

Then a doctor interrupted.

Judah had gone into cardiac arrest again.

They brought him back.

Minutes later, chaos erupted in his room.

“This is too much for his body,” a doctor said. “I’m calling it.”

Judah’s heart stopped for the third and final time.

It could not endure any more.

Judah Levi Brown died at 9:51 p.m. on September 26, 2016.

They buried him the following week.

He was the youngest of seven children.

The only child his parents had together.

Their last baby.

Their Judah-bug.

While sitting helplessly in the PICU, watching her son die, Judah’s mother learned something that filled her with rage on top of grief.

Drowning is the number one cause of accidental death for children ages one to four.

It is the number two cause for children ages four to fourteen.

Boys are seventy-seven percent more likely to drown than girls.

She had never been told this before.

Not by pediatricians.

Not by schools.

Not by parenting books.

Car seat safety is drilled into parents from pregnancy onward — yet drowning is fourteen times more likely to kill a child than a car accident.

Why wasn’t anyone talking about this?

Why did she only learn when her child was already dying?

Out of unimaginable loss, something unexpected began to grow.

Judah’s preschool teacher reached out, wanting to organize a fundraiser to help with the overwhelming medical bills. That small act grew into something much larger — The Judah Brown Project, a foundation built to ensure other parents would never have to learn these lessons the way Judah’s family did.

Today, Judah’s legacy lives on.

Through water safety education.

Through survival swim lessons for families who cannot afford them.

Through pamphlets in pediatric offices across the country.

Through training for parents, caregivers, teachers, and professionals.

Through a message that saves lives.

Because drowning is fast.

Because drowning is silent.

Because puddle jumpers create false confidence.

Because children cannot understand risk the way adults assume they can.

Because real water safety requires multiple layers of protection.

Judah’s story exists so that other children can live.

His life was short.

But his legacy is powerful.

And through every child saved, Judah Levi Brown is still here — still teaching, still protecting, still reminding the world that silence around water can be deadly, and that awareness can mean the differ