“He Wasn’t Even Here Yet, and We Were Already Afraid”: Toby’s Fight From a Shadow on an Ultrasound to a Future Shaped by Science, Courage, and a New Kind of Hope . Hyn

Before anyone had held him, before his first cry or his first breath, Toby had already introduced himself to the world as a question. At twenty-eight weeks’ gestation, a routine scan triggered by a minor fall revealed something no expectant parent prepares for: a fast-growing mass on his upper arm and shoulder. In that instant, the birth plan Jenaya had so carefully imagined—calm, low-intervention, the kind where time is measured in heartbeats and happy tears—shattered into a calendar of appointments, acronyms, and what-ifs. Specialists floated the most comforting possibility first: a vascular birthmark, perhaps a hemangioma. Malignancy? Unlikely, they said. Still, the language of caution settled over the final trimester like a storm.

From then on, life became a carousel of ultrasounds and monitoring. The mass was rich with blood vessels. That mattered, the doctors explained; high vascularity can strain a tiny heart. At night, when the house fell quiet, fear grew its own vocabulary. Would the next scan still show a strong heartbeat? Could the mass rupture? Could a child be lost before anyone knew him? There are few torments like a mother’s imagination once it is given a shadow to fill.

When Toby arrived, relief came first—a healthy cry, warm weight, a living, breathing son. But when the bustle ebbed and Jenaya finally traced her fingers along his arm, the relief met reality. His upper arm was swollen and mottled, knotted with raised segments and deep fissures between them, and a hard lump sat like a shoulder stone at the back. The questions only deepened.

Specialty clinics reviewed his case. Imaging stacked up. The early consensus landed where everyone hoped it would: a rare vascular malformation, but benign. “Not malignant,” someone said, and for a moment the floor steadied. Still, uncertainty clung. Wanting a second look, the family reached out to an international vascular birthmark foundation. The reply was swift and bracing: this didn’t behave like a typical infantile hemangioma. The baby, they urged, needed urgent evaluation.

That nudge became a lifeline. Images were sent to a radiologist at Westmead in Sydney; a nurse there moved mountains to have Toby seen. By the next morning, the phone rang: “Come now. We’ll biopsy and plan.” It is astonishing how quickly a family can pack a life into a bag when a sentence rearranges the future.

The biopsy drew its own line in the sand. The gentle euphemisms fell away, replaced by six plain words that take the air out of a room: malignant spindle cell neoplasm—cancer. An oncologist arrived with another possibility, infantile fibrosarcoma, and a plan for more testing. Jenaya heard her own voice from far away, asking practical questions while a more primitive part of her only registered a single, unendurable thought: am I going to say goodbye before I even know who he is?

As if illness weren’t enough, life piled on. A COVID exposure forced mother and newborn into isolation together, while flooding back home cut off supplies and news of whether their house still stood. Toby, just three weeks old, battled reflux and pain in a ward that had become their entire world. A PET scan followed—the longest hour of Jenaya’s life—ending with one blessed sentence: there was no sign the cancer had spread. The fight, at least, had boundaries.

Central line in, chemo begun. The drip became the metronome of their days. But after two months of therapy, scans told a story that unraveled hope: the tumor was larger. You could see it grow week by week, Jenaya said—the shoulder rising like a tide. The team laid out two doors, both terrible. Door one: amputation of his arm and shoulder girdle to try to outrun the disease. Door two: far harsher chemotherapy with no guarantee it would work or that the cancer wouldn’t leap elsewhere. On her first Mother’s Day, Jenaya sat with the kind of choice no mother should ever face and tried to weigh love against loss.

They chose amputation. Then, two days before surgery—second thoughts and a sliver of time to pivot. The team layered in additional agents. The next scans held steady. The tumor had stopped marching. Not victory, but not defeat. And sometimes, in pediatric oncology, you live between those poles for a long time.

While the chemo kept the fire from spreading, the Zero Childhood Cancer (ZERO) program—the national precision-medicine trial the family had enrolled in—went hunting for sparks. Deep genomic testing revealed a vulnerability, a molecular switch that might respond to

crizotinib, a targeted therapy more often used in other cancers and rarely, if ever, in sarcoma—and certainly not in infants. The science was there; the precedent was not. For the moment, crizotinib remained an idea on the other side of a wall.

Toby pushed through twelve cycles of chemotherapy. With each one came the grinding costs: febrile neutropenia and the panicked sprints back to hospital; transfusions of blood and platelets; admissions for viruses that preyed on a wiped-out immune system; and infections that kept flaring in the very limb they were trying to save. The calendar became a mosaic of beeps and blood counts. The parents learned to read their son’s color with terrifying accuracy, to hear in his cry what the monitors would later confirm.

At eleven months, Toby hit the ceiling for how much chemotherapy a body that small can safely hold. The oncologist made the ask that every family prays someone will make on their behalf—an application to the United States for

compassionate access to crizotinib. Paperwork, case summaries, molecular profiles, signatures. Then waiting, the purest and hardest form of endurance. The answer came back: yes. The first dose, carefully calculated, felt like stepping onto a bridge suspended over a canyon, tethered only by the promise of a mechanism that made sense on paper and the courage to try.

Seven months later, scans drew a new picture: the tumor was shrinking. That once-towering mass at his shoulder had retreated to two centimeters. Between appointments, something equally sacred was happening—Toby was meeting his milestones. He was not just alive; he was living.

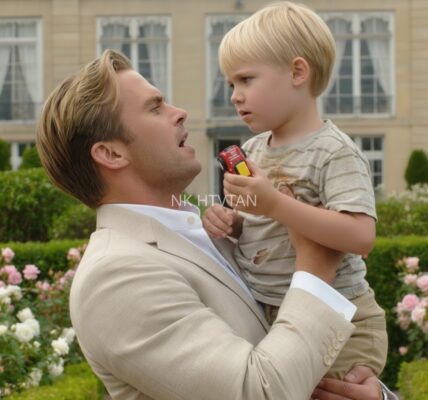

None of this made the path tidy. Crizotinib did not come with a calendar. There was no tidy arc from “start” to “done.” “We’re living scan to scan,” Jenaya said, a sentence that contains both gratitude and grief. The family leaned into ordinary life as if it were the rarest luxury: walks in the neighborhood, coffee with friends, the unremarkable joy of being part of the world again. They pieced together a rhythm at home with a toddler who was once a case and is now simply a child—curious, stubborn, hilarious in the way only one-year-olds can be.

When asked what changed most between conventional chemotherapy and targeted therapy, Jenaya’s answer was not abstract. With chemo, life was punctuated by emergencies. With the targeted drug, life returned. “We can breathe between doses,” she said. It isn’t that side effects disappear; they shift. But in the space created by precision, a family can do the radical thing of being a family.

There were still nights of dread, of course. Parents of medically fragile children learn to sleep like sentries. They keep bags packed by the door. They memorize the sound of their child’s best and worst breathing. And yet, even in that vigilance, they lay claim to joy—first steps recorded on a phone, cake smashed between small fingers, a laugh that erupts exactly when you need it most.

Toby’s story is as much about science as it is about stubborn love. The scan that began it. The biopsy that named it. The genomic testing that mapped a target. The international request that unlocked a molecule. And the team—nurses who slipped comfort into the cracks of long nights, radiologists who returned calls at dawn, oncologists who said “let’s try,” and program coordinators who stitched continents together so a single child might have another option. This is what modern pediatric oncology looks like when it works: not miracle versus medicine, but medicine delivered by people willing to chase a miracle all the way to the edge of precedent.

Jenaya talks now not just as a mother but as a witness. “Too many kids are dying from the treatment,” she says bluntly. It breaks her heart to hear of another child lost not to the tumor but to the toxicity meant to cure it. That’s why she speaks up for research that doesn’t just aim for survival, but for life worth living while you’re surviving—research that finds the lever in a tumor’s wiring and presses there, gently but precisely, so children can spend fewer days in isolation rooms and more days in their grandparents’ arms.

What does hope look like for them today? It looks like a calendar with the next scan circled in a different color than birthdays. It looks like a stroller pushed through a park instead of down a ward. It looks like the ordinary chaos of a toddler tipping out a box of blocks and insisting you help build the tower now. It looks like two parents discovering that going with the flow is not surrender, but a discipline—one you learn when tomorrow is often an essay question, not a multiple choice.

There is no neat ending to offer, not yet. Treatment length remains undefined. The path will bend as new data arrives. But for a boy who once introduced himself as a question mark on an ultrasound, there is a beautiful, stubborn answer in the present tense: he is here. He is growing. The tumor is smaller. The world is larger.

And if you zoom out from one family’s kitchen table to the wider arc of children’s cancer, you can see why their voices matter. Precision programs like ZERO don’t just catalog tumors; they change trajectories. Compassionate access isn’t just administrative kindness; it is a bridge between discovery and a child who needs that discovery now. Partnerships, donations, clinical trials, lab hours that stretch past midnight—these are the quiet verbs that turn “maybe” into “look, he’s walking.”

In the end, Toby’s story is a primer in the anatomy of hope. It starts as a whisper in a dark room—please let the heartbeat still be there—and becomes a chorus: the nurse who says “we’ll make room,” the radiologist who calls at dawn, the oncologist who refuses to let a lack of precedent equal a lack of possibility, the scientist who coaxes a signal from a strand of tumor DNA, the administrator who pushes a paper through so a package can cross an ocean, the parents who hold each other up when the choice is unthinkable, and the child who, despite all of it, learns to clap when the dog barks and to giggle at bubbles in the bath.

He wasn’t even here yet, and they were already afraid. Now he is here—and they are already grateful. The fear hasn’t disappeared; it rarely does. But it’s been joined by something stronger: a way forward that didn’t exist for families like theirs a generation ago. Scan to scan. Step by step. Molecule by molecule.

Somewhere on a living room floor, a one-year-old named Toby is knocking down the tower he just made and demanding you help him build it again. The shoulder lump that once defined the room is now just one part of a much bigger picture. Outside, the world keeps turning. Inside, his parents exhale, then laugh, then reach for more blocks. And in that ordinary, radical moment, you can see the future they’re fighting for—one where treatment buys not just time, but childhood.